This is what architecture, Ji Shi, was thinking about over summer:

“3D printing technology has great potential in future fabrication field however…This manufacturing process has limitations in spatial flexibility and fails to perform a fabrication structural strategy. It is because the current 3D printing technology mostly relies on the superimposition of thermoplastic ABS/PLA material along direction of gravity.”

Shi was in a summer workshop at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning in Shanghai. Its focus was biomimetics, the science that finds inspiration in nature to engineer human-centered solutions. He was trying to show that building techniques already found in nature are increasingly becoming possible for people to replicate. And that thinking led to his team developing a robotics-integrated 3D-printing device that produces self-supporting forms in space – or as he calls it, Robotic 6-Axis 3D Printing, or robotic extrusion.

The material and fabrication method mimics the micro-structure and production of spider silk.

“The spider thread is abstract as a linear material in the centre with three separate and sinusoidal wave shape material attached beside. This change can reinforce the structure,” the team noted in their video.

The strength of a spiderweb comes not only from the careful weaving, but also from the thread itself, which the spider spins in a distinct shape. This shape, the students postulated, could benefit a 3D printed self-supported structure. So they incorporated the spindle-knot shape from nature, hoping to accomplish stronger, more durable self-supporting forms that grew from the ground.

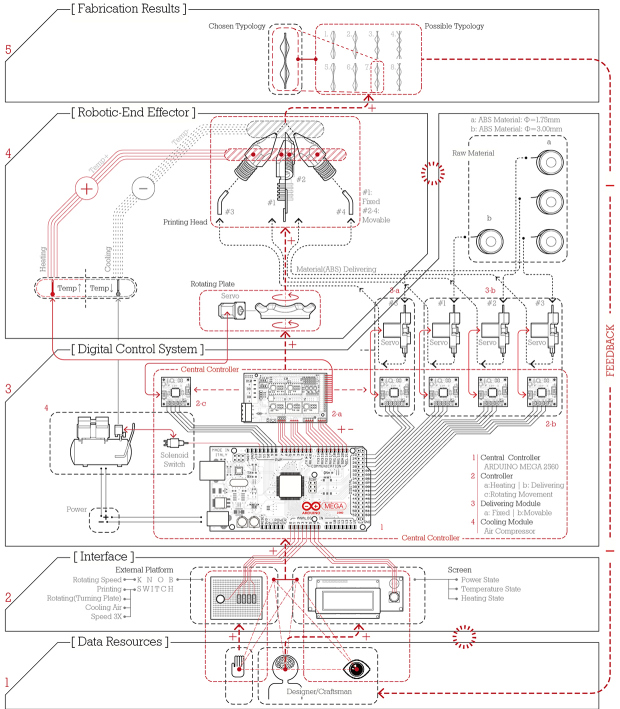

The team still used conventional ABS in their printing. But differed in the second phase. Key to the extrusion process is a Kuka six-axis robot with end effectors to which three mobile print heads are attached, arrayed around a fourth fixed print head.

Their Arduino system includes four servos, which work much like normal 3D printing devices to drive the ABS delivery system, with one motor rotating the central turn-plate. The rotation of the turn-plate causes the movable print heads to oscillate, creating the desired spindle-knot form. Compressed air is sent via tubes to the print heads to cool and set the ABS as it exits the print head, and each print head has its own programmable heater to maintain the right extrusion temperatures. All of the motors and devices are controlled by switches on the center stack of the digital control system.

Printing and rotation speeds can be adjusted to achieve specific structures. All of this was achieved in just three weeks and is now being finessed.